POPULAR GUIDES

Seasonal + Upcoming

Where to Celebrate Lunar New Year Around Seattle in 2025

Slither into a new season 🐍

Date Night Ideas in Seattle: From Rage Rooms to Dessert Crawls

Ditch the dinner date 🔨

A Local’s Guide to Pike Place Market After Dark

Yes, it’s open late 🌝

Where to Get Coffee and Do Work in Seattle

It’s time to WFC (work from coffee shop) ☕

A First-Timer’s Guide to T-Mobile Park

Importantly, where to find the curry donuts 🍛🍩

Where to Sweat Around Seattle

Saunas, steam rooms, hot springs, and hot tub boats 🥵

A Quick Guide to Black-Owned Businesses in Seattle and Tacoma

Buy Black all year long 🛍️

Neighborhood Deep Dives

Five Places to Visit Near the New Lynnwood Light Rail Station

#4 is a 24-hour burrito drive-through 🌯

A Night Out in White Center

Perfectly gritty 🐀

A Weeknight Out in Greenwood

Uniquely Seattle 🍻

Where to Go Before and After a Show in Lower Queen Anne

Records! Oysters! Speakeasies galore! 🦪

An Afternoon Walk Through Beacon Hill

Don’t be pedestrian, be a pedestrian🚶♀️

A Local’s Guide to Shopping in Columbia City

From handmade snacks to Chanel pumps 👠

Food & Drink Adventures

Where to Get Coffee in Seattle

Other than Starbucks ☕️

16 Boba Shops in Seattle’s University District

Boba on every corner 🧋

A Night Out With Friends in Lynnwood’s K-Town

Just off Highway 99 🚗

Where to Buy Weed in Seattle

Where to spend green to get green 🤑

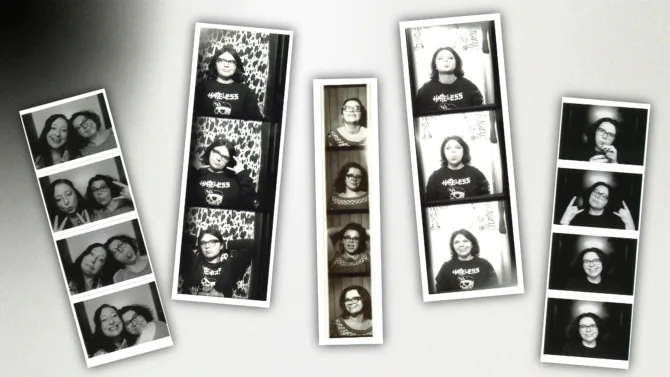

The Best Bar Photo Booths in Seattle

Get pics with your pints 🍺

A Guide to Bar Trivia Nights Around Seattle

A pub quiz for basically every neighborhood ✏️

Cultural Experiences

Seattle’s Coolest Libraries and Archives

Black history, Braille, a Pike Place secret, and much more 📚

SEA Airport Is Basically an Art Gallery

Beauty-starved travelers, this is for you 🖼

A Walk Through UW’s Best Architecture

Get into that green space 🌳

5 Off-The-Beaten-Path Museums in Seattle That Locals Love

From pinballs to log houses 🪵

10 Places Every Grunge Fan Must Visit in Seattle

Seattle does, in fact, smell like teen spirit 🎸

Local Activities & Entertainment

Where to Find Craft Classes and Workshops in Seattle

Get crafty 🧶

Where to Play Board Games in Seattle

Nerds just wanna have fun 🎵

A First-Timer’s Guide to Arcades in Seattle

We’re a pinball capital 🕹️

Where to See Local Standup Comedy in Seattle

A guide to laughs 🤣

Where to Sing Karaoke in Seattle Every Night of the Week

It’s a karaoke singer’s paradise around here 🎤✨

How to WhirlyBall in Edmonds (and… What Is It?)

Let’s get Whirlybuggin’ 🐞

Guide: The Best Dance Studios in Seattle

Choreo, community and core work 🎶